A Design Manifesto, Cultural Analysis, and Postmortem

Introduction

Most tabletop games are designed to deliver stories; My setting, Rosenhall, accumulated history. Most campaigns reset, resolve, or fade; Rosenhall persisted. It remembered.

This document exists because Rosenhall refuses to become nostalgia. Over a decade later, it continues to exert gravitational pull over myself and the people who touched it. Attempts to revive it have repeatedly failed, not because the world was flawed, but because the conditions that allowed it to emerge no longer exist in the same way.

This is not an attempt to provide advice, nor to romanticize adolescence. It is an analysis of authority, trust, emotional risk, rules literacy, and social context in tabletop roleplaying. It is written for experienced Dungeon Masters who sense that something fundamental has changed in the hobby, but struggle to articulate what was lost and why.

Rosenhall mattered because it was honest. It did not protect players from themselves. It did not validate power. It did not smooth over consequence. It allowed the world to respond truthfully to godlike violence wielded casually. The sections that follow examine the structural conditions that made Rosenhall possible, why those conditions were transient, and what forms of stewardship remain viable now.

Rosenhall Was a World, Not a Campaign

Rosenhall was never experienced as a campaign that went particularly well. It was experienced as a place that existed, stubbornly, whether the players were present or not. That distinction matters more than any mechanical choice or narrative technique. Most tabletop games, even very good ones, are structured around delivery. The world exists to support story beats, character arcs, and climactic moments. When the campaign ends, the world dissolves. Its relevance was conditional on play.

Rosenhall never dissolved.

What made Rosenhall compelling was not its lore density, its originality, or even its drama, though it had all three. It was compelling because it accumulated consequence in a way that could not be unwound. Towns were not reset after arcs. Institutions did not conveniently forget what had happened to them. Characters did not revert to archetypes once their narrative function was complete. Rosenhall remembered. And because it remembered, it began to behave like a real place instead of a narrative container.

I’ve described Rosenhall to new players as “walking on a beach where the sand is filled with the footprints of everyone who came before.” That metaphor has stayed with me because it captures something authored settings almost always lack: residue. In Rosenhall, history was not something written in a sidebar. It was something you tripped over. It was the reason a city reacted coldly. It was the reason an institution existed in a compromised form. It was the reason common folk flinched instead of cheering when adventurers entered a room.

This was not intentional worldbuilding. It was reactive worldbuilding. The setting was not designed to explore themes of power, fear, or authority. Those themes emerged because the players exercised power freely and the world was allowed to respond honestly. Rosenhall was not asking, “What story do I want to tell?” It was asking, again and again, “What would this place look like if this really happened?”

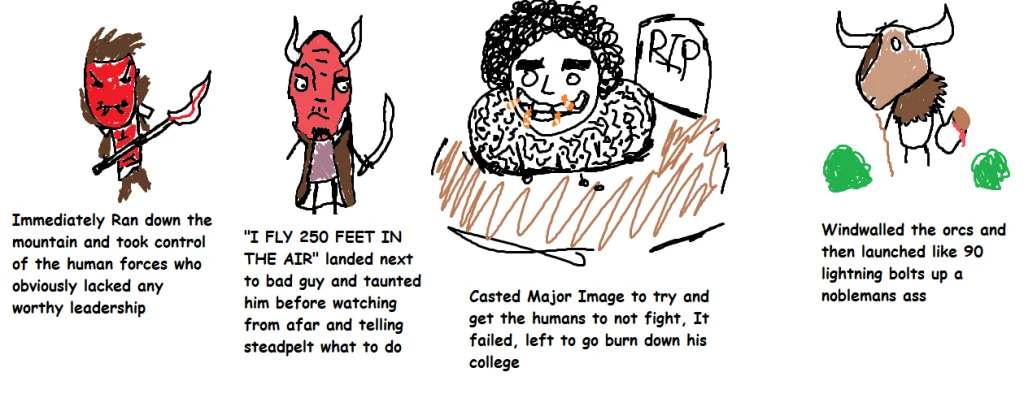

My first players, “The Vanguard”, are the clearest example of this distinction. They were not written as morally gray antiheroes. They were not conceived as tyrants, villains, or tragic figures. They were heroes, truly heroes, who believed, sincerely, that good should triumph over evil, and that they were uniquely qualified to decide what that meant. The danger of the Vanguard was not cruelty. It was certainty.

After stopping a serial killer, the Vanguard demanded a reward from the crown: a private island. The government agreed. On that island, the Vanguard built a massive tavern, an explicit declaration of autonomy, status, and permanence. They were no longer adventurers passing through the world. They were a fixture within it, operating on terms they had negotiated themselves.

The tavern was staffed, among others, by a vampire working toward “redemption.” When tax collectors were eventually sent to the island, the vampire killed them. Responsibility dissolved instantly. It was the vampire’s fault, not the guild’s. The institution remained untouched. This pattern repeated itself throughout Rosenhall: power outsourced its consequences and remained clean.

A man who disrespected the Vanguard was taken as a slave and made quartermaster “to teach him respect.” When he was finally released a decade later, Garrus, the de facto leader, remarked that the man should be thankful. He had been paid well. This was not framed as cruelty at the table. It was framed as pragmatism. That framing mattered. Rosenhall allowed the justification to stand, and then allowed the world to internalize what that justification meant.

Several towns became collateral damage in the pursuit of cultists. One town was burned to the ground over a ten-gold toll the Vanguard deemed unjust. Later, when sent by the crown militia to suppress an orc rebellion, they decided the orcs were right, and slaughtered the militia instead, striking down the crown prince himself with divine lightning. Eventually, they discovered the queen was a lich, assassinated her, and teleported away from prosecution. No trial. No public reckoning. Just absence.

In a conventional campaign, any one of these events might have been treated as the climax of an arc, followed by narrative realignment. Rosenhall did not realign. It adapted.

Governments learned that laws existed only as long as adventurers allowed them to. Cities learned that enforcement was symbolic. Civilians learned that heroism was something to stand far away from. Newspapers became propaganda not because of ideology, but because fear needed a language.

This is where Rosenhall permanently diverged from authored fantasy. Authored worlds tend to reward intervention. Rosenhall punished it socially, slowly, and irreversibly. And crucially, it did so without collapsing the game. There was no divine retribution. No sudden pivot into villain-campaign territory. The world simply began to behave as though adventurers were not a public good, but a destabilizing force that had to be managed, avoided, or survived.

That restraint was the most important design choice Rosenhall ever made, even if it was accidental. A realistic military response would have ended the game. A moralizing response would have cheapened it. Rosenhall instead chose continuity. The world kept going, wounded and wary, because it still needed these people, even as it feared them.

This is why, years later, every other setting feels boring to me. It isn’t that other worlds lack imagination. It’s that they lack memory. They have not been lived in long enough to grow scar tissue. They have not been shaped by the unrepeatable chemistry of real people making bad decisions repeatedly and being allowed to live with them.

Rosenhall is not special because it was better written. It is special because it was barely written at all, not in the way settings usually are. It was inhabited. It was argued with. It was harmed. It was disappointed. It carries the emotional weight of people who are no longer at my table but are still present in the world they helped distort.

Boarding School, Constant Presence, and the Closed Headspace

Rosenhall did not emerge in a vacuum. It emerged in a very specific social container, and that container mattered just as much as any narrative decision I made behind the screen. The fact that this game was played at a boarding school is not a charming anecdote or a nostalgic footnote. It is the single most important structural reason Rosenhall worked at all. Strip that context away, and much of what people later described as “good DMing” collapses under inspection. What remains is not technique, but environment.

At boarding school, we did not merely meet once a week to play a game. We lived together. We woke up together, ate together, sat through classes together, and returned to the same dorms at night. The social loop never reset. There was no clean psychological boundary between “game time” and “real life.” Characters, conflicts, grudges, philosophies, and plans were always present, simmering quietly in the background of everyday life. Rosenhall did not require re-immersion at the start of each session because we never fully left it.

This constant presence created what I’ve come to think of as a closed headspace. The game had no competition for attention once the Wi-Fi went down, which it did nightly at 11:00PM. No phones. No social feeds. No parallel dopamine streams. When play began, it was the most interesting thing happening in the room by default. Engagement was not something I had to earn through spectacle or pacing tricks; it was structurally enforced by boredom everywhere else.

That enforced attention changed everything. When modern DMs talk about player distraction, about people scrolling during scenes, half-listening, or needing constant stimulation, I recognize the problem, but I don’t recognize the environment. Rosenhall did not exist alongside ten other stimuli. It existed alone. If you wanted novelty, excitement, or surprise, the table was where you got it.

This environment also fundamentally altered how time functioned in the campaign. Because we lived together, we could offload logistics into the margins of the day. Shopping didn’t need to happen at the table. Planning didn’t need to consume session time. We handled those things during study hall, over lunch, or in passing conversations. If someone wanted to roleplay buying supplies or negotiating a contract, we could do it informally and quickly. That freed our nightly sessions, often six to eight hours long, to focus almost exclusively on the moments that mattered: dangerous decisions, moral arguments, combat, betrayal, fallout.

More importantly, it allowed for private play in a way I’ve almost never seen replicated since. During free blocks, a player and I would disappear into my dorm room and roleplay a one-on-one scene for forty-five minutes: a lover’s argument, a mentor’s confession, a secret pact, a quiet moment of doubt. Those scenes were not performed for the table. They were not immediately shared. They remained secrets until the player chose to reveal them, or not. The world deepened asymmetrically. Knowledge became uneven. Trust mattered.

Modern safety discourse often frames secrecy as inherently dangerous. In Rosenhall, secrecy was what made relationships feel real. It worked because the social environment already provided safety. We lived together. We knew each other’s boundaries intuitively, not procedurally. No one needed a checklist to know when they had gone too far; that feedback existed socially, instantly, and continuously.

The rhythm of play mattered too. Because sessions happened (almost) every night, momentum compounded instead of decaying. Emotional arcs did not cool off over six days of real life. Conflicts carried forward with heat intact. Decisions made one night were still emotionally present the next. Characters evolved quickly, not because of mechanical progression, but because they were being inhabited continuously.

This is something adult weekly play struggles to replicate no matter how skilled the DM is. When sessions are separated by a week or two, emotional memory fades. Players forget not just details, but feelings. Stakes have to be re-established repeatedly. Scenes that would have landed with devastating force in a continuous environment feel muted after a long pause. Rosenhall did not suffer from that entropy. It never had time to.

Even the technical limitations of the time reinforced this dynamic. I ran maps off a laptop plugged into a flat-screen TV laid on my desk, an improvised setup built by our robotics teacher. If I needed fog of war or lighting, the party took a ten-minute snack break while I drew lines. There was no pressure for polish. No expectation of perfection. The world moved at the speed of our attention, not the speed of our tools.

Looking back, it’s tempting to attribute Rosenhall’s success to youth, energy, or raw talent. That’s comforting, but it’s also misleading. What actually made the game work was density. Density of time. Density of attention. Density of shared context. The boarding school environment compressed all of that into a crucible where consequences could accumulate faster than comfort could dissolve them.

This is why attempts to recreate Rosenhall in adult life feel hollow by comparison. It’s not that players care less or that I’ve forgotten how to tell stories. It’s that the container has changed. Adult life fractures attention relentlessly. Online play multiplies exits. Safety mechanisms replace trust because trust no longer has time to form organically. The closed headspace is gone.

Rosenhall did not teach me how to run games. It taught me something more unsettling: that some forms of play are not portable. They depend on conditions that cannot be recreated on demand. They emerge once, burn brightly, and leave behind something that feels impossible to repeat, not because the magic is gone, but because the world that allowed it to exist has moved on.

That realization is uncomfortable. It forces a reckoning not just with design, but with loss. And it sets the stage for the next, harder truth: why the people at that table could endure the kind of play Rosenhall demanded, and why many adults cannot.

Adolescence vs. Adulthood: Emotional Elasticity, Risk, and Identity

One of the hardest truths to articulate about Rosenhall, especially to adult players who want to believe the difference is purely about style or preference, is that the game worked in part because we were teenagers. Not because we were reckless, or because we didn’t care, or because we were somehow tougher. It worked because adolescence comes with a kind of emotional elasticity that adulthood quietly erodes, and Rosenhall demanded that elasticity constantly.

As teenagers, our sense of self was not yet fully entangled with competence. Failure did not immediately translate into judgment. A bad roll was frustrating, but it wasn’t humiliating. A dead character was disappointing, but it wasn’t an indictment of intelligence or preparation. Consequence landed hard in Rosenhall, but it didn’t linger as shame. It became story. We metabolized it socially and moved on.

That distinction matters more than most discussions of “old school vs. modern play” ever acknowledge. Rosenhall did not protect players from loss. Characters died. Reputations collapsed. Entire moral frameworks were exposed as hollow. The game asked players, repeatedly, to live with the outcomes of decisions that felt reasonable in the moment and disastrous in retrospect. As teenagers, we could absorb that without internalizing it as a personal failure.

I don’t think this was virtue. I think it was context.

Teenagers, for all their volatility, often have fewer entrenched identities. We were still experimenting with who we were allowed to be. That experimentation extended naturally into play. A character could make a catastrophic choice without the player feeling like their intelligence, creativity, or social standing at the table was being evaluated. The emotional stakes were high, but the ego stakes were relatively low.

That is no longer true for many adult players, and that isn’t a flaw, it’s a consequence of living in a precarious world.

By the time most people return to tabletop games in adulthood, they are carrying exhaustion, insecurity, and a profound lack of authority from other parts of their lives. Jobs offer little autonomy. Politics feels inaccessible. Economic stability is fragile. In that context, the game table becomes one of the few spaces where control feels achievable, and system mastery becomes the mechanism by which that control is exercised.

This is where optimization stops being a playstyle and starts becoming identity.

When a character’s effectiveness is deeply tied to a player’s sense of competence, any threat to that effectiveness feels personal. Damage isn’t just damage; it’s invalidation. A ruling isn’t just a ruling; it’s an accusation. An enemy adapting to a tactic isn’t narrative logic, it’s hostility.

I’ve felt this shift directly. In Rosenhall, players would take eight damage from eating bad shrimp at a low-class tavern and laugh. In later games, I’ve watched players with impenetrable defenses argue that a single Dexterity save was “toxic” because it undermined their build. The mechanics hadn’t changed. The emotional context had.

That moment, where a Bladesinger with an AC of 30 accused me of “countering their character” because enemies stopped swinging swords at an unhittable target, is not actually about balance, fairness, or even encounter design. It’s about escape. More specifically, it’s about the kind of escape adult players often seek from tabletop games, and what happens when that escape is disrupted.

For many adult players, D&D functions as a controlled power fantasy. It is a space where competence is rewarded reliably, where preparation guarantees success, and where mastery of a system produces dominance that the real world often withholds. The fantasy is not just about being powerful, it’s about being unquestionably powerful. Being correct. Being optimized. Being insulated from surprise.

When that fantasy is subverted, when enemies adapt, when a different axis of threat appears, when the world refuses to cooperate with the expectation of invulnerability, the reaction is rarely framed as “the fiction responding logically.” It is experienced as intrusion. As unfairness. As being forced back into a reality where control is conditional and authority can be challenged.

That Bladesinger wasn’t reacting to points of damage. They were reacting to the collapse of a promise they believed the game had made to them: that if they built correctly, the world would comply. When it didn’t, the experience stopped being escapist and became threatening. The system no longer insulated them from uncertainty, it mirrored it.

In Rosenhall, that kind of investment would have been impossible to sustain. The world did not reward perfection consistently enough. Power worked, but it worked dangerously. It created fear. It created collateral damage. It created moral fallout. You could not hide behind your build, because the consequences of your actions were not confined to hit points and saving throws.

And crucially, no one at the table was emotionally fragile enough to demand that the game protect them from that truth.

I want to be very clear here: this is not a condemnation of modern players. It is a recognition that adult life often strips people of safe places to fail. When you have very little authority in the real world, asserting authority over a ruleset can feel necessary. When you are rarely allowed to be wrong without consequence, a game that punishes mistakes can feel cruel rather than honest.

Rosenhall did not offer safety in that sense. It offered trust.

We lived together. We knew where the real lines were. If someone crossed one, it was handled socially and immediately, not procedurally. There were no pauses for group processing, no extended negotiations about tone, no formal recalibration of expectations. The response was blunt and unambiguous.

If someone got upset to the point of disrupting play, we didn’t stop the game. We kicked them out into the hallway for the night and kept playing without them.

That sounds harsh when described in isolation, but it only worked because of the environment it existed within. We were not strangers meeting once a week. We were a shared social organism. Being removed from the table was not exile, it was a cooling-off period enforced by peers who would see you again at breakfast. The consequence was real, but it was temporary and social, not moralizing or permanent.

That kind of enforcement required trust, trust that no one was being malicious, trust that the group’s continuity mattered more than any one moment of discomfort. It also required emotional elasticity. People could be excluded briefly without interpreting it as rejection or betrayal. The game moved forward, and the social fabric repaired itself naturally.

Modern tables rarely have access to that mechanism. When play is infrequent and relationships are thin, exclusion feels catastrophic. So procedure replaces trust, and safety replaces resilience. Rosenhall never needed that replacement, not because we were kinder, but because we were closer.

Authority, Epistemic Control, and the Death of Appeal

If adolescence explains why Rosenhall’s style of play was survivable, authority explains how it functioned moment to moment. Not authority in the sense of dominance or ego, but epistemic authority: the question of who, at the table, has the power to decide what is true right now. Rosenhall worked because that question had a clear answer, and because that answer could not be deferred.

In Rosenhall, it never occurred to anyone to argue with the DM. That isn’t because I was especially intimidating, charismatic, or correct. It’s because the structure of play made appeal impractical. There was no Wi-Fi. There were no open tabs. There was no instant access to exact wording, edge cases, or designer intent. Paper character sheets summarized abilities loosely. Memory was fallible. Interpretation was necessary.

Most importantly, the world responded immediately.

When something happened, it happened before anyone could stop it. Before anyone could say “actually.” Before anyone could search. Fiction resolved faster than meta. Consequence arrived before negotiation. That temporal relationship, fiction first, appeal impossible, is the single most important design element Rosenhall ever had, and it was almost entirely accidental.

Modern play has inverted that relationship.

Today, rules are omnipresent. Not just available, but ambient. D&D Beyond, 5etools, searchable PDFs, Autofill options on VTT character sheets, all of them exist in the background, quietly asserting a claim: that the game’s reality is not located at the table, but in the text. The DM no longer speaks with finality; they speak provisionally, pending verification.

This is what I mean when I say epistemic authority has fractured.

In Rosenhall, when I described an effect, that description was the effect. In modern play, the description is a hypothesis. It can be challenged, cross-referenced, escalated. Even when no one says anything out loud, the possibility of appeal lingers. I can feel it. The pause. The hesitation. The sense that what I’m saying exists under review.

That sensation alone is enough to kill momentum.

Appeal culture does not need to be exercised to be corrosive. Its mere availability changes behavior. Players begin to hedge. DMs begin to qualify. Fiction becomes cautious. Decisions are delayed just long enough for the system to reassert control.

This is where the phrase “rulings over rules” is often invoked, but rarely interrogated deeply enough. The issue is not whether DMs should improvise. The issue is speed. Rosenhall’s rulings worked because they were immediate and irreversible. They did not invite comparison. They did not linger as debates. They landed.

That speed allowed for brutality without cruelty.

One of the clearest examples happened in a tavern, late in the Vanguard’s rise. The party was already powerful, well past the point where most threats felt meaningful to them, but they did not yet feel powerful. A Minotaur druid, frustrated by the lack of combat, decided to start a bar fight. Out of game, it was meant as flavor. In game, it was a single horn strike against a commoner.

At that level, the damage was trivial by adventuring standards. To the common man, it was catastrophic. The blow killed him instantly. Not dramatically. Not heroically. Horribly.

There was no bar fight.

The room went silent. No one attacked the Minotaur. No one reached for a weapon. The surviving patrons just stared, frozen, waiting to see if they were next. The player reacted with shock: “shit”, in the same way someone does when they realize, too late, what they’ve done. In that moment, everyone at the table learned something about scale, power, and fear that no rules explanation could have conveyed.

That lesson could not have survived even a thirty-second delay.

In a modern game, that moment would almost certainly have been intercepted by appeal. “Reaction: Nonlethal damage.” “I didn’t mean to kill him.” “Can I choose to pull the blow?” Each of those statements is reasonable within a rules-first epistemology. Each one also erases the very thing that made the moment meaningful. In Rosenhall, there was no time for erasure. The action resolved. The consequence landed. The world reacted.

A similar incident occurred later with an Aasimar paladin. Drunk, belligerent, and being dragged out of another tavern by Garrus, he activated Radiant Scourge in a moment of anger. Radiant energy tore outward through a crowded room. Commoners died instantly. Guards rushed in and, for once, actually posed a threat, this was a higher-level city with trained forces. Garrus panicked and killed them to save the paladin. The party fled. The city formally banned them, because it had no other recourse.

On paper, Radiant Scourge has exact dimensions. Its radius is precise. Its damage is known. In Rosenhall, what mattered was not the text, it was the event. Divine power erupted in a space built for ordinary people, and the result was mass death. The world responded to that, not to a rules citation. Adventurers everywhere became more frightening because of it.

Modern tools would have shrunk that moment until it fit neatly inside acceptable parameters. Rosenhall let it spill.

This is the core tension: modern systems increasingly promise safety through precision. Exact wording. Exact ranges. Exact outcomes. That precision is comforting, especially for players who are already guarding themselves emotionally. It creates predictability. It guarantees fairness. It ensures that investment yields reliable returns.

But it also eliminates terror.

Terror requires uncertainty. It requires not knowing exactly how far something reaches, who it might catch, or whether intent matters once power is unleashed. Rosenhall’s authority structure preserved that uncertainty because no one could appeal fast enough to neutralize it.

Appeal culture also flattens failure. When every outcome is negotiable, failure becomes optional. Not avoided through play, but avoided through process. If something goes wrong, it can be paused, discussed, reframed, or undone. Over time, players learn, consciously or not, that the game will protect them from catastrophic misunderstanding.

Rosenhall never offered that protection.

That doesn’t mean it was unfair. It means it was honest about power. When you act with godlike force, the world does not wait for you to check the fine print. It reacts.

The tragedy of modern play is that many DMs feel this loss but blame themselves for it. They prep harder. They buy better maps. They commission music. They run Foundry servers on cloud machines. And still, players scroll. Still, engagement fractures. Still, every ruling feels like a potential argument.

The problem is not effort. It is authority.

Rosenhall’s authority was not earned through correctness. It was enforced through structure. No appeal meant no delay. No delay meant consequence. Consequence meant meaning.

That structure no longer exists by default. Reclaiming it requires explicit buy-in, and even then it is fragile. As long as the rules exist one click away, the possibility of appeal remains, hovering over every decision like an unspoken threat.

This is why modern games so often produce “perfect wins.” Not because players are smarter, but because the system now guarantees insulation from the unknown. Every edge case can be neutralized. Every danger can be quantified. Every loss can be explained away.

Rosenhall did not allow that. It did not because it could not.

And in that inability, born of technical limitation, social trust, and speed, something rare emerged: a world where decisions mattered because no one could take them back once the world had answered.

That is what was lost when appeal became infinite.

Imperfect Knowledge and Narrative Violence

Once authority is established and appeal is no longer immediate, something subtler begins to emerge at the table. Not balance. Not fairness. Something far more dangerous: violence whose meaning is not fully known at the moment it is committed. Rosenhall’s most powerful moments did not come from clever tactics or overwhelming force. They came from hesitation, players acting without certainty about what would happen next.

Imperfect knowledge did not make Rosenhall chaotic. It made it human.

Paper character sheets forced players to understand their abilities the way people understand power in the real world: approximately. Players knew what they could do, but not all the ways the world might respond when that power was unleashed in a living environment. That gap between intent and outcome is where narrative violence lives.

Modern systems work tirelessly to close that gap. Exact wording, exact ranges, exact interactions exist to ensure that nothing truly unexpected occurs. The result is safety, but also sterility. Violence becomes transactional. Harm becomes something you deploy correctly or incorrectly, rather than something you unleash and then reckon with.

Rosenhall allowed violence to surprise the people committing it.

That difference became devastatingly clear after the Vanguard murdered the Crown Prince.

The world did not respond theatrically. It responded intelligently. The crown deployed the Taimavar, elven special forces trained not to confront the Vanguard directly, but to destroy what anchored them. They did not seek a climactic battle. They burned down the Vanguard’s original Guildhall and systematically murdered their NPC allies.

In a modern game, that scene would likely collapse under precision. There are dozens of ways, used “correctly”, to extinguish a fire instantly. Countless spells that could end the encounter in a single, optimized action. But precision creates confidence, and confidence removes fear. Rosenhall offered no such certainty.

Faced with the burning Guildhall, the players hesitated. Not because they lacked power, but because they feared using it incorrectly. They did not know whether a spell would smother the flames, feed them, collapse the structure, or kill the very people they were trying to save. So instead of solving the encounter, they ran into the fire.

They fought through smoke, screaming, and collapsing beams. They watched allies die while trying to reach others. In the midst of that chaos, one of the Vanguard attempted to end the assault with overwhelming force, a Fireball, thrown not as geometry, but as desperation.

A Taimavar soldier threw himself into the blast. The explosion tore him apart and saved the rest of his unit. The spell worked, and in doing so, revealed its cost. Violence interrupted violence. Meaning was decided after the fact.

By the time the night ended, the Guildhall was gone. Most of their allies were dead. The Vanguard did not “win.” What they managed to do was save The Prophet, a sorcerer NPC, their first quest giver, who teleported them to safety. From a distance, they watched their home collapse into ash.

That moment became the emotional backbone of the second half of the campaign. It marked the end of safety, the end of permanence, and the world’s declaration that power would now be answered in kind. Arc Two did not begin because of a plot hook. It began because the players survived something they could not cleanly solve.

Imagine if that scene had been played “correctly.” Imagine if one spell, applied with perfect knowledge, had erased the entire enemy force. Imagine if someone had said “um, actually,” and the fire went out, the building stood, and every ally lived.

The story would have ended right there.

Rosenhall’s violence mattered because it could not be optimized away without fear. Players could act, but they could not guarantee the meaning of their actions in advance. The world reserved that right.

Modern play often treats misunderstanding as failure. Rosenhall treated it as revelation. When players misunderstood the scope of their power, the world responded honestly, and that response taught them something permanent, not about rules, but about responsibility.

Violence becomes narratively powerful when it cannot be fully anticipated. When power is comfortable, it becomes a toy. When power is uncertain, it becomes something you carry carefully, knowing it might cost more than you intended.

Rosenhall never asked players to be reckless. It asked them to accept that acting in the world means accepting that the world may read your actions differently than you hoped.

If any of this feels uncomfortably familiar, it’s probably because you’ve lived the opposite experience.

You’ve prepped a session carefully. You’ve built tension, layered NPC motivations, sketched out a location meant to take half the night to explore. And then, twenty seconds in, it’s over. A spell fires. An ability resolves. A perfectly executed sequence of actions unfolds exactly as written. The encounter dissolves. The mystery collapses. The stakes evaporate. What was supposed to be the backbone of the session becomes a speed bump.

In moments like that, it’s easy to assume the problem was preparation. That you failed to anticipate the right spell. That you didn’t account for some interaction buried three layers deep in a digital character sheet. That if only you had planned better, if only you had internalized every edge case, every ruling, every designer clarification, this wouldn’t have happened.

But that assumption is a trap.

The real issue isn’t that you failed to prepare for every spell being applied perfectly, instantly, and in the exact wording exported from FoundryVTT into the chat window. The issue is that the game has quietly redefined mastery in a way that leaves no room for uncertainty to breathe. Players now arrive at the table with access to every ruling, every specification, and an effectively infinite archive of clarifications, errata, and vague Jeremy Crawford tweets they can invoke the moment friction appears.

When something goes wrong, when the world pushes back in a way that wasn’t expected, you’re left with two options. You can accept the appeal and let the moment collapse. Or you can resist it and trigger an argument that can only end one way: with you saying “I don’t care,” asserting authority explicitly, and damaging trust in the process.

Neither option feels good.

This is the hidden cost of total system mastery. When the game becomes perfectly knowable, it becomes perfectly solvable. And when it becomes solvable, it stops having bones. Stakes turn hollow. Consequences flatten. Prep becomes a guessing game where the DM is expected to function less like a storyteller and more like a rules engine that failed to account for a rare input.

At that point, the table isn’t asking you to be a person anymore. It’s asking you to be a computer.

That’s why these moments feel so demoralizing. You’re not watching your story fail, you’re watching the game reassert itself as something closer to Baldur’s Gate 3, where the fun comes from executing systems efficiently, and the world exists primarily to validate correct inputs. The players aren’t malicious. They’re playing the game they’ve been taught to expect.

Rosenhall could never become that game, because it never promised solvability. It never offered an “I win” button that worked reliably. Power was dangerous precisely because it was not perfectly understood, and violence mattered because it could not be safely applied without fear.

If you’ve ever felt something go missing when your prep evaporates under perfect execution, the answer isn’t that you failed. It’s that the structure of modern play has quietly replaced uncertainty with certainty, and certainty, no matter how fair, cannot sustain meaning for very long.

That doesn’t mean you need to reject modern tools or shame modern players. It means you need to understand what kind of game those tools are quietly building, and what kind of game they make impossible.

Rosenhall lived in that impossibility.

The Vanguard: Power, Fear, and Consequence Without TPKs

One of the most persistent misunderstandings about Rosenhall, especially when described secondhand, is the assumption that it must have been a relentlessly punitive game. That, if the world responded honestly to power, then surely that response would have taken the form of overwhelming force. Armies. Assassins. Gods. A campaign-ending reckoning. In other words: a TPK disguised as realism.

That never happened. And the fact that it didn’t is the reason Rosenhall survived long enough to become what it did.

The Vanguard were not punished into submission. They were absorbed by the world in a way that fundamentally changed how the world behaved. This distinction matters. Mechanical punishment ends games. Social consequence sustains them.

From the outside, the Vanguard looked like something out of myth: an adventuring party that could burn towns, kill princes, assassinate monarchs, and simply leave. The natural instinct, both for readers of the story and for many modern DMs, is to ask why the world didn’t “do something about them.” Why the crown didn’t muster an army. Why the gods didn’t intervene. Why the game didn’t end.

The answer is that the world did do something about them. It just didn’t do the thing that would satisfy a sense of symmetrical justice.

Rosenhall understood something that many games miss: power does not provoke direct confrontation as often as it provokes avoidance. When an actor becomes too dangerous to confront openly, systems adapt around them. They don’t escalate until victory is guaranteed. They change routes. They build redundancies. They withdraw cooperation. They let the problem exist, contained, feared, and isolated.

After the Vanguard slaughtered the crown militia and struck down the prince, the political reality of Rosenhall shifted permanently. The question was no longer “How do we stop them?” It became “How do we survive in a world where they exist?”

Cities banned them. Not as a symbolic gesture, but as a practical one. Governments stopped asking for their help unless absolutely necessary. Laws were rewritten quietly to exclude “extraordinary actors.” Newspapers reframed their deeds not as heroics, but as instability. The Vanguard did not become enemies of the world, they became weather. Something you prepared for. Something you routed around.

This was not moral judgment. It was risk management.

That approach preserved play because it refused escalation for its own sake. A realistic military response might have felt satisfying, but it would have been suicidal. An army that could challenge the Vanguard directly would, by definition, have ended the campaign. Rosenhall avoided that dead end by allowing institutions to behave the way institutions actually do when faced with overwhelming force: they retreat into procedure, distance, and denial.

The result was far more unsettling than open war.

The Vanguard were never “hunted down.” They were cut loose. Their island tavern still stood, but it existed in a political vacuum. Their actions still mattered, but fewer people were willing to be near them. Allies became liabilities. Associations became dangerous. Their reputation preceded them not as legend, but as warning.

This is why the Taimavar strike worked as well as it did. It wasn’t retaliation. It was surgical removal of support. The world didn’t try to kill the Vanguard. It killed what made them human.

That distinction, between targeting the actors and targeting the structures around them, is what allowed Rosenhall to remain playable without softening its stance on consequence. The Vanguard were not absolved. They were isolated. And isolation is a far more enduring punishment than death in a game where resurrection exists.

It also preserved player agency.

At no point did the world say, “You are villains now.” It said, “This is what it costs to keep doing this.” The Vanguard were still free to act. They were still powerful. But every action narrowed the space in which they could safely exist. The world did not stop them, it made them lonely.

That loneliness mattered. It forced introspection without forcing repentance. It allowed the players to feel the weight of their choices without stripping them of control. Rosenhall never demanded that the Vanguard become better people. It demanded that they live in the world they had made.

This is the core lesson many modern games struggle to internalize: consequence does not need to be lethal to be final. It needs to be persistent. It needs to reshape the environment in ways that cannot be solved with a spell slot or a clever build.

When consequence is purely mechanical, players learn how to optimize around it. When consequence is social, political, and reputational, optimization becomes irrelevant. You can’t min-max your way back into trust. You can’t rules-lawyer a city into welcoming you. You can’t “win” your way out of being feared.

Rosenhall leveraged that truth relentlessly.

The Vanguard became legendary not because they were unstoppable, but because the world learned it could not afford to stop them directly. And in doing so, Rosenhall avoided the trap that ends so many “realistic” campaigns: escalation to annihilation.

Instead of ending the story, consequence deepened it.

This is why Rosenhall could sustain godlike power without collapsing under it. It treated power not as something to be countered, but as something to be lived with. The world adapted. The players adapted. The game continued.

And in that uneasy equilibrium, where no one truly won and no one was ever safe, the setting became something rare: a living system that could absorb extraordinary violence without breaking.

That is not leniency. That is design.

And it is the reason Rosenhall lasted as long as it did, while so many more “balanced” worlds shatter the moment players become too strong.

Why Rosenhall Cannot Be Recreated (And Why That’s Okay)

The hardest truth to accept about Rosenhall is also the most important one: it cannot be recreated. Not fully. Not honestly. Not without breaking the very conditions that made it possible in the first place. Every attempt I’ve made to revive it over the last decade, every reboot, sequel, and soft continuation, has confirmed that fact more clearly than the last.

And for a long time, I treated that as failure.

I assumed that if I just found the right group, the right tools, the right cadence, I could bring it back. That the magic was in the setting, the lore, the factions, the philosophy. That if I preserved those elements carefully enough, the rest would follow. What I eventually had to confront was that Rosenhall was not a product of design alone. It was an artifact of circumstance.

It emerged from a moment in time that cannot be reproduced: adolescence, shared living space, constant presence, limited external distraction, and a table culture that prioritized momentum over comfort. Rosenhall did not grow slowly. It accreted nightly. It lived in the same mental space as school, friendships, conflict, boredom, and exhaustion. It was not something we visited once a week. It was something we inhabited.

Adult life does not allow for that kind of density.

Modern play is fragmented by necessity. Schedules are brittle. Attention is divided. Sessions are isolated events rather than chapters in a continuous experience. Even when games last for years, they are often emotionally episodic. You remember what happened last session, but you don’t live in the aftermath the next morning. The connective tissue is thinner.

That doesn’t make modern games worse. It makes them different.

The mistake is trying to force Rosenhall to exist under conditions it was never designed for. Every reboot that struggled, every group that burned out, every friendship strained over mismatched expectations reinforced the same lesson: this kind of world demands more than most adult tables can, or want to, give.

That doesn’t mean it was wrong to try.

Some of the later games came close. Rosenhall 2 had moments that felt like the old days. The final Rosenhall campaign, Tales from the Sapest, came closer than anything else, precisely because it embraced intensity rather than convenience. Multiple sessions a week. Long arcs. Emotional commitment. And still, even that game fractured under pressures that didn’t exist when we were sixteen.

What changed wasn’t just the players. It was the cost of consequence.

As teenagers, consequence stayed in the game. As adults, consequence bleeds outward, into friendships, into self-image, into the need for safety and validation. What once felt like dramatic tension now risks feeling personal. What once felt like challenge can feel like threat. Rosenhall asks players to accept loss without appeal, ambiguity without reassurance, and authority without arbitration. That is a tall order when the game is no longer the center of your social world.

This is the part that is hardest to say out loud: Rosenhall worked not just because of trust, but because of containment. The game was the dominant shared reality. There was nowhere for the emotions to go except back into the fiction. When someone was upset, it stayed inside the circle. When something hurt, it was metabolized collectively. Adult life does not permit that kind of closure. There are too many exits.

Recognizing this reframes the entire project. Rosenhall is not a model to be scaled. It is not a system to be optimized. It is not proof that modern players are doing it “wrong.” It is evidence that certain kinds of stories require conditions that are no longer broadly available.

And that realization, while painful, is also liberating.

Because it means Rosenhall does not need to be fixed, modernized, or made compatible with contemporary expectations to justify its existence. It already succeeded. It already did the thing it needed to do. It produced a living world, lasting memories, and a generation of players whose understanding of agency, power, and consequence was permanently altered.

Trying to recreate it perfectly is a form of denial.

Letting it stand as an artifact, a once-in-a-lifetime campaign born of impossible conditions, is an act of respect.

Conclusion: Rosenhall as Artifact, Not Blueprint

Rosenhall is not a system. It is not a method. It is not something that can be packaged, exported, or reliably reproduced. Treating it as a blueprint, something to be followed step by step, is the fastest way to misunderstand what it was and why it mattered.

Rosenhall was an artifact.

It was created under conditions that no longer exist in the same form: adolescence, constant proximity, limited external authority, shared boredom, shared risk, and a table culture that valued momentum over safety and trust over arbitration. The world that emerged from those conditions was not “better designed” than modern games. It was denser. It had fewer exits. When something happened, everyone had to live with it together.

That density is what gave the setting weight.

Modern tabletop culture is not wrong for moving in a different direction. The rise of safety tools, system mastery, and explicit consent reflects real needs. Many players come to the table seeking refuge, stability, or control in a world that offers very little of it. Games that promise fairness, clarity, and protection are responding to that demand honestly.

But those promises come with tradeoffs.

When every outcome is knowable in advance, violence loses its capacity to surprise. When every ruling can be appealed, authority becomes negotiable. When every edge case is pre-litigated, consequence becomes optional. And when the DM is expected to function as an impartial processor of inputs rather than a human interpreter of a world, something essential goes missing.

That loss is what many disillusioned DMs feel, even if they struggle to name it.

Rosenhall names it by absence.

It shows what happens when uncertainty is allowed to persist, when power is dangerous because it is not fully understood, and when the world is permitted to respond socially and politically rather than mechanically. It demonstrates that consequence does not need to be lethal to be lasting, and that fear of one’s own power can be a source of meaning rather than frustration.

Most importantly, it demonstrates that living worlds demand something modern play rarely asks for: restraint.

Rosenhall required players to trust that the DM was not acting maliciously, even when outcomes hurt. It required them to accept loss without immediately seeking redress. It required them to value the continuation of the world over the perfection of a single moment. Those are not trivial demands. They are not compatible with every table, and they should not be imposed on players who do not want them.

That is why Rosenhall cannot, and should not, be universal.

Its value lies not in replication, but in reflection. It exists to remind us that some kinds of stories only emerge when control is limited, when knowledge is imperfect, and when authority is exercised sparingly but decisively. It stands as a counterexample to the idea that more rules, more clarity, and more protection always produce better play.

They produce safer play. They produce fairer play. But they do not always produce meaningful play.

Rosenhall did not survive because it was optimized. It survived because it was trusted. Because its players accepted that the world could hurt them without hating them. Because its DM was allowed to be a person, not a referee bound by appeal.

That kind of trust is rare. It cannot be demanded. It can only be grown under the right conditions, and those conditions are not always available.

Which is why Rosenhall matters now.

Not as a standard to be enforced, but as a memory that sharpens critique. A reminder that when games feel hollow, the problem may not be the players, the prep, or the system, but the quiet disappearance of uncertainty, authority, and consequence in favor of comfort.

Rosenhall does not need to be revived to justify itself.

It already answered the question it posed.

And the fact that it can no longer be recreated may be the most honest thing it ever taught.